Counting the Omer: Are We Really like the Sotah?

The Important Connection Between Sefirat ha-Omer and Silence

It is taught in a Mishnah (Sotah 2:1): כָּל הַמְּנָחוֹת בָּאוֹת מִן הַחִטִּין וְזוֹ בָאָה מִן הַשְּׂעוֹרִין. מִנְחַת הָעֹמֶר אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁבָּאָה מִן הַשְּׂעוֹרִין הִיא הָיְתָה בָאָה גֶרֶשׂ וְזוֹ בָאָה קֶמַח (All minchah offerings are made from wheat, but this one [i.e. the sotah's minchah offering] is from barley. The minchah offering of the omer, even though it's made from barley, it is made from geres [finely ground and well-sifted barley], but this one [the sotah's offering] is made from kemach [i.e. coarsely-ground up and left unsifted]). Explaining why the sotah's offering must be made from barley described as 'kemach', Rabban Gamliel says: כְּשֵׁם שֶׁמַּעֲשֶׂיהָ מַעֲשֵׂה בְהֵמָה כָּךְ קָרְבָּנָהּ מַאֲכַל בְּהֵמָה (Since she behaved like an animal, her offering is animal food).

But what about the omer offering? Since it was also made from barley, we might come to think that just as we have behaved like animals, so too our offering should be food for animals. But Rabban Gamliel doesn't say that. Why not? The Mishnah makes a distinction. Even though the two offerings are made from barley, they aren't the same. One is from barley that is coarsely-ground up and left unsifted, while the other is from highly-refined barley flour. Although Rabban Gamliel teaches us the deeper meaning behind the sotah's offering, he doesn't say anything about the omer offering.

Let's see what we can learn from the fact that the minchah of the omer is made from highly-refined barley flour.

As is brought down in many sefarim, the days of counting the omer are days of teshuvah. How can we assess the quality or level of our teshuvah to determine where we are holding? R' Nachman gives us a clear answer (Likutei Moharan 6:2): וְעִקַּר הַתְּשׁוּבָה כְּשֶׁיִּשְׁמַע בִּזְיוֹנוֹ יִדֹּם וְיִשְׁתֹּק (The essence of teshuvah is: When one hears his disgrace, he remains silent and quiet). When one hears himself being insulted, disgraced, humiliated or embarrassed – not only in private, but even publicly – and he doesn't try to defend himself, or respond with a 'good come back', or even get angry, but rather remains silent, then he'll know just how much of a ba'al teshuvah he really is.

Furthermore, it is taught there in L.M. 6:2: וְזֶה בְּחִינַת כֶּתֶר, כִּי כֶּתֶר לְשׁוֹן הַמְתָּנָה (And this [i.e. teshuvah] is an aspect of [the sefirah of] keter [כֶּתֶר], for keter indicates 'waiting'). How do we know that these three ideas – teshuvah, keter and waiting – are all connected together? Reish Lakish taught (Yoma 38b): בָּא לִטָּהֵר מְסַיְּיעִין אוֹתוֹ (Someone who comes to purify [himself], they help him). The School of R' Yishmael taught a mashal to help us internalize the idea. It's comparable to a person who comes into a fragrance store to buy some perfume. The merchant, however, is busy with another customer, so he politely says to the customer: הַמְתֵּן לִי עַד שֶׁאֶמְדּוֹד עִמְּךָ כְּדֵי שֶׁנִּתְבַּסֵּם אֲנִי וְאַתָּה (Wait for me so I can measure it out with you, so that you and I can be perfumed). Now, purifying oneself clearly indicates doing teshuvah. So although this shows that teshuvah is exemplified by the attribute of waiting patiently, how does this relate to the sefirah of keter? When Elihu came to speak with Iyov, he said to him – in Aramaic – (Iyov 36:2): כַּתַּר־לִי זְעֵיר וַאֲחַוֶּךָּ (Katar for me a little bit and I will tell you). And what does katar mean? Rashi says: כָּתַר לְשׁוֹן הוּחַל (Katar indicates 'waiting').

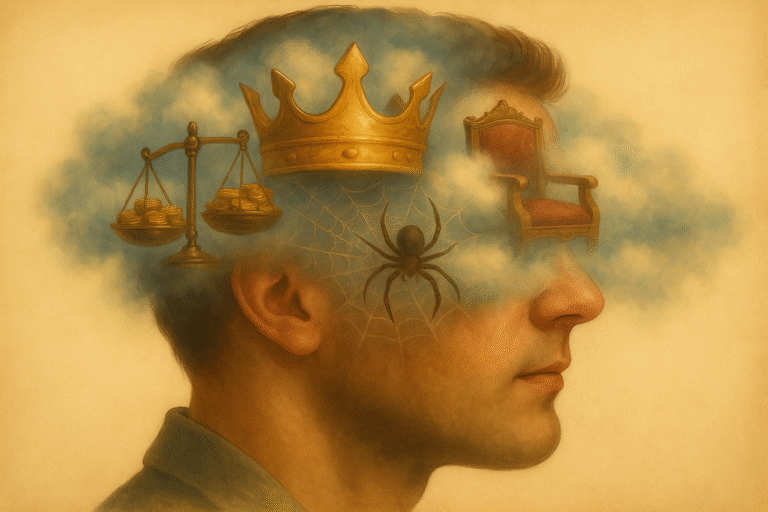

This is how R' Nachman knew that teshuvah is in keter – because the essence of teshuvah is being patient and not speaking back, especially when people insult, disgrace or embarrass us (L.M. 6:2): וְתִקּוּן לָזֶה שֶׁיַּהֲפֹךְ דַּם לְדֹם שֶׁיִּהְיֶה מִן הַשּׁוֹמְעִים חֶרְפָּתָם וְאֵינָם מְשִׁיבִים וְלֹא יְדַקְדֵּק עַל בִּזְיוֹן כְּבוֹדוֹ וּכְשֶׁמְּקַיֵּם דֹּם לַה (And the rectification for this is that one should turn blood [dam] to silence [dom], that he'll be among those who hear their disgrace and don't respond [see Rashi on Tehillim 38:14], and doesn't make a big deal about insults to his honor, for then he fulfills 'silence [dom] to Hashem' [Tehillim 37:7]). And what is the blood spoken of here? It is the blood that is spilled when someone is insulted, embarrassed or humiliated, as taught by Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak in the Gemara (Bava Metzia 58b): כׇּל הַמַּלְבִּין פְּנֵי חֲבֵירוֹ בָּרַבִּים כְּאִילּוּ שׁוֹפֵךְ דָּמִים (Anyone who insults the countenance of his fellow in public is like he is spilling [his] blood [i.e. it is like he's killing him]). This is the blood that we must learn to convert to silence – dam to dom. Anyone who can reach this level will not only merit the sefirah of keter in Olam ha-Zeh, but will also merit to wear a crown, sitting on a throne of glory in Olam ha-Ba .

What does any of this have to do with the omer offering?

R' Natan in Likutei Halachot explains this topic and starts by mentioning a point about teshuvah which we stated above (Hilchot Sefirat Ha-Omer 1:1): וְהִנֵּה יְמֵי הַסְּפִירָה, שֶׁהֵם יְמֵי תְּשׁוּבָה (Behold, the days of counting [the omer] are days of teshuvah). But when did the process of teshuvah begin? R' Natan answers: שֶׁהוּא תְּחִלַּת הַתְּשׁוּבָה שֶׁיּוֹצְאִין מִן הַסִּטְרָא אָחֳרָא בְּחִינַת יְצִיאַת מִצְרַיִם וְאָז הִיא בְּחִינַת הַבָּא לִטָּהֵר מְסַיְּעִין לוֹ כִּי בְּפֶסַח עִקַּר הַתְּשׁוּבָה עַל-יְדֵי סִיּוּעָא דִּלְעֵלָּא עַל-יְדֵי הִתְעוֹרְרוּת עֶלְיוֹן (It [Pesach] is the beginning of teshuvah, that we come out from the Sitra Achra, in the aspect of coming out from Egypt, and then it is the aspect of 'the one who comes to purify himself, they help him out' [Yoma 39a], for at Pesach, the essence of teshuvah is through Help from Above, through a Supernal Awakening).

He is making a very important point. As is known, there are two kinds of awakenings, an Awakening from Above [אתערותא דלעילא, itaruta dil’eila] and an Awakening from Below [אתערותא דלתתא, itaruta dil'tata]. When Hashem initiates and reaches out to us, so to speak, that's called an Awakening from Above, but when we, so to speak, initiate and reach out to Him, that's called an Awakening from Below. Pesach corresponds to the Awakening from Above – Help from Above – itaruta dil’eila. This should make sense since Hashem brought us out of Egypt on His own accord after dishing out plague after plague upon Egypt.

What did we see already? When someone comes to purify himself, i.e. to buy the perfume – to do teshuvah, i.e. an Awakening from Below – itaruta dil'tata – what is he told? He is told to wait: הַמְתֵּן לִי עַד שֶׁאֶמְדּוֹד עִמְּךָ (Wait for me so I can measure it out with you). Therefore, we see that there must be a period of waiting after the initial awakening, i.e. after Pesach. This corresponds to the days of counting the omer in which we wait seven weeks before receiving the Torah. Therefore, even though Pesach and the days of counting the omer are both times for teshuvah, Pesach corresponds to an Awakening from Above whereas the days of counting the omer correspond to an Awakening from Below. This Awakening from Below is absolutely critical because it actualizes the teshuvah which came to us as a gift from Hashem during Pesach.

But let's not misunderstand. This 'waiting' isn't an impatient kind of waiting, like we may experience while waiting to get to the front of a queue. Rather, this 'waiting' is typified by patience – patience in working on ourselves, on working to nullify all of the bad character traits which hold us back from becoming who we were meant to be. At least, that's the ideal. In other words, this 'waiting' is an active process, ascending higher and higher each and every day, according to the character trait, i.e. the middah, that is relevant for that day. The Ba'al Shem Tov explains this with a mashal of a little boy learning to walk. At first, his daddy holds his hand and makes sure that he doesn't fall down. But in time, the daddy lets go because his little toddler has to learn to walk on his own. This is the difference between the Awakening from Above and the Awakening from Below, between Pesach and the days of counting the omer.

Now we come to the minchah of the omer.

What is the essence of the teshuvah that we need to actualize during the days of the counting of the omer? Let's read further in Likutei Halachot: וְעִקַּר הַתִּקּוּן עַל-יְדֵי הַבּוּשָׁה עַל-יְדֵי הַדְּמִימָה וְהַשְּׁתִיקָה כְּמוֹ שֶׁמְּבֹאָר שָׁם וְזֶה בְּחִינַת עֹמֶר שְׂעוֹרִים שֶׁהוּא קָרְבָּן מִמַּאֲכַל בְּהֵמָה שֶׁזֶּה בְּחִינַת הַתְּשׁוּבָה שֶׁעִקָּרָהּ עַל-יְדֵי הַבּוּשָׁה כַּנַּ"ל עַל-יְדֵי דְּמִימָה וּשְׁתִיקָה כַּנַּ"ל (The essence of the rectification is through embarrassment [or 'shame'], i.e. through silence and being quiet, like it is explained there [in Likutei Moharan 6], and this is the aspect of the omer of barley which is an offering made from animal food, that this is an aspect of teshuvah, the essence of which is through embarrassment, as mentioned above, through silence and quietness, as mentioned above).

What is the main focus of this embarrassment? R' Natan continues: וּכְמוֹ כֵן בִּפְרָטִיּוּת בָּאָדָם עַצְמוֹ עִקַּר הַתְּשׁוּבָה כְּשֶׁמִּתְבַּיֵּשׁ לְפָנָיו יִתְבָּרַךְ וְעוֹשֶׂה עַצְמוֹ כִּבְהֵמָה שֶׁאֵינָהּ מְדַבֶּרֶת כִּי אֵין לוֹ פֶּה לְדַבֵּר לֹא מֵצַח וְכוּ' מֵחֲמַת בּוּשָׁה כְּמוֹ שֶׁאִיתָא בְּרַעֲיָא מְהֵימָנָא שֶׁזֶּה עִקַּר הַתְּשׁוּבָה כְּשֶׁאָדָם אוֹמֵר אֵין לִי פֶּה לְהָשִׁיב וְכוּ' מֵחֲמַת בּוּשָׁה וְעוֹשֶׂה עַצְמוֹ כִּבְהֵמָה אֲזַי נֶחֱשָׁב כְּקָרְבָּן (And like this, in particular, with man himself, the essence of teshuvah is when he is embarrassed before Him, may He be blessed, and makes himself like an animal that doesn't speak, for one can't open his mouth to speak or lift his forehead, etc. because of embarrassment, like it is brought down in the Ra'aya Mehemna [Zohar ha-Kadosh, Mishpatim 119a], that this is the essence of teshuvah – when a man says, 'I have no mouth to respond, etc.' because of embarrassment, making himself like an animal. Then it's considered an offering).

This is also as David ha-Melech wrote (Tehillim 38:14): וַאֲנִי כְחֵרֵשׁ לֹא אֶשְׁמָע וּכְאִלֵּם לֹא יִפְתַּח־פִּיו (And I am like a deaf man that can't hear, and like a mute who doesn't open his mouth). And Rashi explains on that pasuk: ישראל שומעים חרפתם מן המחרפי' ואינם משיבים ולמה כי לך הוחלתי שתגאלני ותושיעני מהם (Yisrael hears their disgrace from those who disgrace her, but they don't respond. And why? Because, 'To You I wait [huchalti], that You will redeem me and save me from them'). Again, this is the aspect of waiting that we saw earlier – כַּתַּר־לִי זְעֵיר וַאֲחַוֶּךָּ – where Rashi says – see above – that katar means waiting [הוּחַל, huchal]. But as we said earlier, not just ordinary 'waiting', but active waiting, more like 'longing' or 'yearning'.

Although the minchah of the sotah and the minchah of the omer are both made from barley, and so represent an animal, they represent two different aspects of an animal – one negative and one positive. This explains why Rabban Gamliel only explained the sotah's offering in negative terms, likening her to an animal with respect to promiscuity. However, with respect to the omer, he did not make a comparison. Despite the fact that the offering is barley, i.e. it still relates to an animal, the symbolism is very different. Here, it's a positive comparison, comparing the inability of an animal to speak with the inability of a ba'al teshuvah to speak. And why isn't a ba'al teshuvah able to speak, i.e. to Hashem? Because he realizes the sheer enormity of his sins and feels embarrassed. This distinction also explains why the sotah's minchah is made from kemach, i.e. coarsely-ground and unsifted barley, which is only suitable for animals, but the omer is made from geres, i.e. highly-refined and sifted barley flour, suitable for humans.

This explanation gives us insight into a somewhat incomprehensible prayer of David ha-Melech (Tehillim 58:2): הַאֻמְנָם אֵלֶם צֶדֶק תְּדַבֵּרוּן (Indeed, will a mute speak justice?). How can a mute person speak? By definition, he can't speak. Let's read how Likutei Halachot explains it: כְּשֶׁאָמְנָם וֶאֱמֶת שֶׁהוּא אִלֵּם כִּי אֵין לוֹ פֶּה לְדַבֵּר וְכוּ' כַּנַּ"ל, אֲזַי צֶדֶק תְּדַבֵּרוּן, אֲזַי יִפְתַּח פִּיו וִידַבֵּר כִּי הַשֵּׁם יִתְבָּרַךְ מְקַיֵּם: פְּתַח פִּיךָ לְאִלֵּם (When it is 'indeed' and true that he is 'mute', for he has no mouth to speak, etc. as mentioned above, then 'he will speak justice', for then He will open his mouth, and he will speak, for Hashem, may He be blessed, will fulfill, 'Open your mouth for the mute' [Mishlei 31:8]).

In conclusion, we have seen that when one makes himself mute in the face of insults or other forms of disparaging comments – this being the essence of teshuvah – he comes to resemble an animal who cannot speak. Such a person merits the sefirah of keter, which is likened to a crown, thus being truly worthy of receiving the Torah at Shavuot. And this explains why the two loaves of Shavuot are made from wheat [חִטָּה, chittah] instead of barley. The gematria of חִטָּה is 22, corresponding to the number of letters in the aleph-bet. It is as the Zohar ha-Kadosh says about the word 'waving', i.e. תְּנוּפָה [tenufah], that is a necessary aspect of the acceptance of this offering (Balak 118b): תְּנוּ פֶּה [Tenu peh] – Give us a mouth!

May we merit to pray to Hashem: "We have long been mute. We have been disgraced, insulted and embarrassed, and kept quiet. You have seen our disgrace, but You have also seen our heartfelt teshuvah. Hashem, open our mouth. Give us a mouth and let us speak again! Let the period of silence be over. We are not animals. We have become Adam."

For at Shavuot, the process of teshuvah will have been made complete.